Intellectually high-flying though it be, LLNL nonetheless sits on ordinary earth with some intractable historical problems. The Laboratory’s square mile hosted a naval air station in the mid- to late-1940s, when concern over fuel spills and hazardous materials was off radar. In the 1950s, seepage from landfills and operations introduced volatile organic compounds, fuel hydrocarbons, metals, and tritium into the groundwater, threatening regional aquifers. In 1987, cleanup of the main Livermore site was placed on the Environmental Protection Agency’s “National Priorities List,” with the more remote Site 300 joining in 1990.

The Laboratory accordingly established the Environmental Restoration Department (ERD) to remove contamination, and an existing program was expanded as the Environmental Functional Area within the Environment, Safety and Health Directorate to mitigate harmful effects going forward.

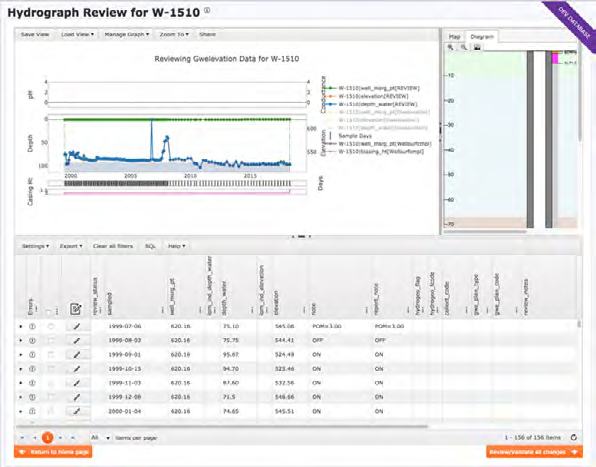

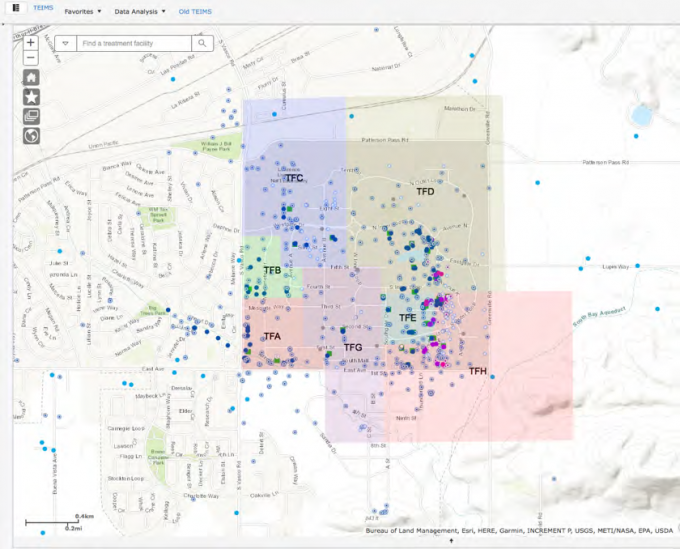

Software was needed to track environmental data, so Excel and some independently developed applications were gradually consolidated into a system for collaborative tasks, site characterization, modeling, risk assessment, decision support, operations tracking, compliance monitoring, and regulatory reporting. The resulting Taurus Environmental Information Management System, or TEIMS, also monitors LLNL’s performance in applying environmental technologies to the DOE/NNSA long-term stewardship program.

In sum, TEIMS enables the systemic migration of ideas and data through the environmental-data lifecycle: from regulatory requirements to modeling, data analysis, planning, sampling, physical sample analysis, quality assurance, verification, field operations, regulatory reporting, and back to modeling and analysis.

The software has undergone many laborious, multiyear overhauls since inception in the 1990s. Notable redevelopments include the migration of databases to Oracle, consolidation of standalone apps, normalizing database tables, and migration to Linux. Periodic updates to hardware, databases, languages, and functionality have consumed additional years.

The current challenge is converting the TEIMS backend language from Perl to Python. Before plunging in, however, the team took a good look at the whole picture. Gary Laguna, a senior architect for environmental software systems, recounts, “We need software that can endure. With all TEIMS efforts in mind, great and small, we asked, ‘can we do better?’”

The team acknowledged that hitting every software goal over the anticipated service life—seven or more decades—was unattainable. Hardware, software, and infrastructure evolve, not to mention customer requirements and funding. “This will not be the last redevelopment,” concedes Laguna. Nevertheless, the team decided on a radical redesign aimed at extreme longevity, outstanding agility for incremental adaptation to changes, and high sustainability to reduce support costs in fiscally lean years.

The first decision was to rebuild TEIMS on a service-oriented architecture, which implements shareable, independent modules that provide a function or service through a shared protocol. This allows component development in whatever computer language best fits the task and resources, without affecting modules or applications. Modules are a reusable resource across TEIMS and can be exposed to other systems; and components and applications can consume components and functionality from other systems with the same data-communication protocols, yielding enormous efficiencies.

The team also analyzed infrastructure and development toolchains for reliability and continuity. Among improvements on tap are virtualization of servers, containers that allow automatic movement of code into production, automated testing, and—invaluable for system support in lean years—continuous integration of automatically tested code and automated monitoring and configuration.

“This is a comprehensive effort. We’re adopting many industry standards, practices, and technologies. Where possible, individual components are developed as independent and reusable, even outside the environmental domain. Technologies are shared with ERD’s financial-planning system, Metis,” says John Consolati, TEIMS refresh project co-leader.

The design will allow new mobile capabilities, integration with other LLNL organizations, and migration of Laboratory prototypes into production applications. The team may release non-domain-specific system components as open source software for use in DOE and the environmental-remediation and monitoring field, and share microservices once a proposed LLNL repository becomes reality.

“Our approach is lightweight and applies to proof-of-concept, prototype, and software redevelopment projects,” says Consolati, “so that most major upgrades, improvements, and migrations will be done incrementally, with little user awareness.”

Environmental stewardship is an NNSA performance goal for Lawrence Livermore National Security, LLNL’s management and operating contractor. Some objectives will take decades to achieve; others will continue indefinitely, as reflected in restoration funding that extends nearly to 2100. The TEIMS effort will solidify the Laboratory’s lead in environmental-information management at DOE and NNSA labs. Though many sister labs have resorted to commercial products to manage their data, it’s a risky move, chancing potential business failures or failure to meet evolving requirements.

Laguna stands by the team’s plan: “We value the ability to accommodate and evolve with change, for a reasonable resource and time expense, far beyond our own working lifetimes at the Lab.” TEIMS work is performed through partnership of the ERD and the Environmental Functional Area, and the team regularly participates in Computing's hackathons.